TL;DR—As low-cost air quality monitoring becomes increasingly common in urban environments, there are important considerations to take into account when implementing a sensor network. This includes where to site sensors, how to properly calibrate them, and how to engage community members in the data outcomes they produce. This blog summarizes the valuable insights that our webinar panelists shared about best practices for deploying low-cost sensors in urban environments—as well as the data we gathered from nearly 200 attendees about how they see sensors contributing to the future of air quality monitoring.

In June 2021, we held our “Best Practices for the Use of Low-cost Sensors to Expand Air Quality Monitoring Coverage in the Urban Environment” webinar to promote further conversation around emerging air quality monitoring technologies and their applications in cities and metropolitan areas. The webinar saw nearly 200 attendees, including many air quality experts with 41% of these attendees already managing a low-cost air quality network today.

Word cloud: Job titles of webinar attendees

A further 65% of poll respondents reported that they plan to establish a low-cost or hybrid air quality network in the next year—demonstrating the strong momentum building for low-cost sensors in 2021.

Given the momentum for low-cost sensor technology that we have observed here at Clarity, we thought we would introduce the concept of the technology adoption curve and ask attendees where they thought low-cost sensor technology falls on this curve. The overwhelming majority of respondents (58%) said they thought that air sensor technology is currently in the “early adopters” stage of the curve—a stage at which forward-looking organizations begin to adopt a new technology due to its ability to help them achieve outcomes that were not possible with traditional technologies.

Given the number of attendees already managing a sensor network—and because low-cost air quality sensors can be deployed for such a wide range of uses—we also asked our attendees to report which use cases that they are most interested in using sensors for.

58% of poll respondents reported being interested in using low-cost sensors to raise public awareness, and 56% reported being interested in using the technology to inform environmental and public policy recommendations.

51% of respondents had a desire to use low-cost sensors for environmental justice. To learn more about environmental justice issues in California and how low-cost air quality monitors can serve as a tool to bolster support for environmental equity, check out our environmental justice blog here. It is important to note that achieving desired environmental justice outcomes requires a lot more than just data—effective community organizing, data analysis, and translation to policy outcomes are all key components of a successful environmental justice initiative that can be supported, but not replaced, by air quality data.

45% of respondents reported interest in establishing a hybrid air quality monitoring network using a combination of federal reference or federal equivalent method monitors (FRM/FEM) and low-cost sensors. Hybrid networks allow air quality managers to leverage the strengths of both technologies—low-cost sensors can be implemented at high resolution to serve as indicators of air quality trends at a greater number of sites, and the integration with FRM/FEM data allows the low-cost sensors to be calibrated against federal-grade instruments for improved accuracy. To learn more about this approach you can download our Guide to Leveraging Low-Cost Sensors for Air Quality Monitoring 2.0.

36% of respondents stated that they were interested in using low-cost sensors for non-regulatory supplemental and informational monitoring (NSIM) use cases, meaning that these sensors would be used to collect non-regulatory grade air quality data. This data may be used to directly inform residents of high air pollution or otherwise supplement existing decision-making when it comes to air quality.

36% of respondents also reported having an interest in emergency and/or rapid deployment of low-cost air quality sensors. For example, Brightline Defense in San Francisco deployed a network of monitors prior to the devastating 2020 fire season to allow them to measure corresponding air pollution spikes and advise their residents of pollution levels—as well as actions they should take to reduce exposure. You can read more about Brightline’s deployment here.

Drawing on the expertise of a panel of air quality experts

Our panelists brought decades of experience using low-cost air quality monitors in the urban environment and shared their perspectives on what it takes to successfully implement, manage, and communicate a low-cost sensor network.

Dr. Gary Fuller, an air quality scientist, works with the Breathe London project to place air quality monitors in hospitals, schools, and other sensitive receptors in London. These low-cost air quality sensors are integrated into a hybrid network, meaning they complement existing regulatory city networks in London. Dr. Fuller stresses the importance of making air quality data something available and accessible to the public, such as through the widgets and user-friendly web pages that the project utilizes.

Dr. P. Grace Tee Lewis is the Senior Health Scientist at Environmental Defense Fund. Dr. Lewis prioritizes using low-cost sensor technology for air quality monitoring networks at the community level. She has particularly worked with the Pleasantville community in Houston, Texas which bears a high pollution burden. The project incorporates participatory action from local residents to ensure that the network is well-adapted to the needs and wants of the community.

Michael Ogletree, Air Quality Technical Services Manager at the Department of Public Health & Environment for the City and County of Denver, is also working to deploy a hybrid air quality monitoring network. The Love My Air Denver program places low-cost air quality monitors in schools—a site that would not usually be serviced by a federal monitor—and makes this data available to students, staff, and other community members through real-time data dashboards. Ogletree also shared some unique uses that low-cost sensors have been utilized for, including an odor sensor pilot and deployment at a Black Lives Matter demonstration.

Dr. Meiling Gao (Mei) is the Chief Operating Officer at Clarity Movement, where she is building relationships with government and corporate partners to transform how air quality data is collected and used. She was previously a USAID Global Development Fellow in Colombia and a Fulbright Scholar in China where she conducted research on the impacts of urban development on air quality and health. Mei has a depth of experience with low-cost sensor networks, having worked closely with Clarity’s partners to implement dozens of networks in more than 55 countries around the world.

Framing the conversation: What are the biggest challenges to successfully implementing a low-cost air sensor network?

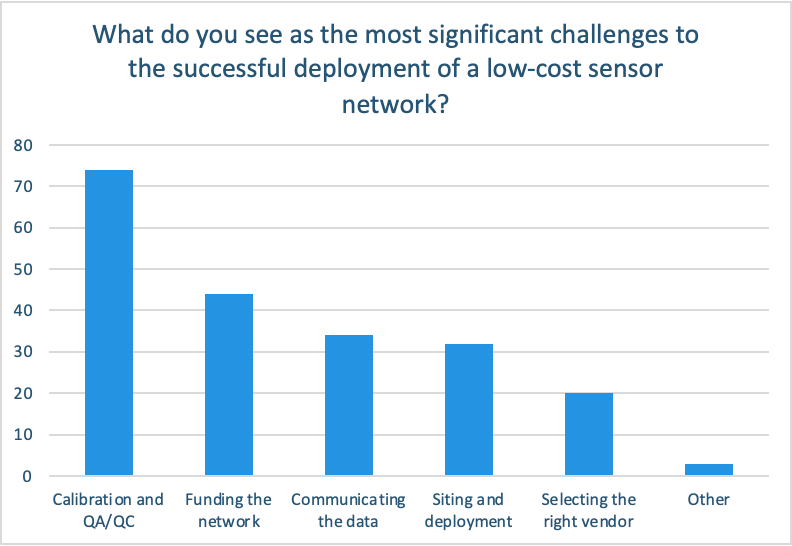

To set the stage for a conversation around best practices, we asked attendees what they consider to be the biggest challenges when implementing air quality monitoring networks. Drawing on the knowledge and experience of our panelists, we worked to provide answers to these challenges and support those setting up monitoring networks, especially with respect to the unique considerations that come when installing them in urban environments.

The greatest percentage of attendees identified calibration and QA/QC as the most significant challenge to successfully deploying a low-cost sensor network. Because low-cost sensors can differ in data quality compared to federal and reference-grade monitors, calibration is an essential part of effective low-cost sensor use. To learn more about Clarity’s Remote Calibration process, check out our Guide to Accurate Particulate Matter Measurements with Air Sensors.

Attendees also stated that funding the network and communicating data findings presented challenges when planning a low-cost monitoring network. Particularly when deploying sensors as part of a community group or environmental justice project, finding sufficient funding and presenting data findings to a non-technical audience are important considerations. To learn more about how low-cost sensors are used by environmental justice communities in California, read our blog here.

The audience also reported that siting and deploying sensors can be a significant challenge. Especially in urban environments, finding siting locations that are appropriate for the goals of the monitoring project takes ample planning and consideration. You can read more about the best practices for siting and deploying low-cost monitors in urban environments here.

Now, we will delve deeper into the different challenges that come along with deploying low-cost air quality monitors in urban environments and share our panelists’ knowledge and experiences on the topic.

How to Choose Monitoring Sites

What information should you collect when designing a network to ensure that sensors are sited in the optimal location? Is it important to involve local community members in this conversation?

Where to place low-cost air quality monitors is a vital consideration when setting up a monitoring network, especially in an urban environment where pollution may differ drastically within the same locale and be affected by a variety of natural and human-related factors. Being sensitive to the needs and concerns of local residents is also crucial in developing a network that serves its community.

Apart from placing sensors near pollution sources, collecting input from the individuals actually living in these communities provides valuable information about pollution concerns. Dr. Lewis’ work in Pleasantville highly values input from local community members when making siting decisions. The network design prioritizes sensitive locations in the community, such as schools, parks, and senior living facilities, and incorporates input collected from residents on sensor placement during community meetings. She emphasizes that it is important to place these monitors in locations that are both meaningful to community members and city and local officials, and can help support data collection of important pollution trends.

Dr. Fuller and Michael Ogletree agreed that it is important to consider residents’ air pollution concerns when siting air quality monitors. In London, this consisted of a competition in which groups could apply to have a node placed in their community. By giving community members an active voice in this decision, they can be more empowered to take ownership of their local air quality.

Calibration & QA/QC of Data

Like any infrastructure, these networks need to be maintained. What are some QA/QC checks and calibration processes you’re implementing on your sensors and the data at the start and then how are those done over the lifetime of these networks? How often should calibration models be subject to a performance review for potential improvement?

Calibration is a major component of gaining accurate insights from low-cost air quality monitoring data. Our panelists agreed that carrying out colocation before deploying a network—and sometimes also throughout the network’s operation—is essential in order to ensure the most accurate data possible with a low-cost sensor network. In an urban environment, the local and seasonal conditions in the specific city are also important factors to account for when developing a calibration model.

Dr. Fuller described the two-stage colocation process that Breathe London sensors go through to ensure that the calibration model takes into account a variety of factors that affect air quality calibration, including relative humidity, temperature, and ambient pollution levels. The network implements real-time corrections to data and includes time periods with higher pollution spikes to ensure that the calibration model functions during outstanding air quality events too.

Similarly, Michael Ogletree emphasized the importance of diligent calibration practices. The Denver low-cost air quality monitoring network calibration includes colocating sensors at 3 FEM sites to carry out both short- and long-term calibration of data. Because of the city’s climate, accounting for seasonal changes in temperature, humidity, and particle variation is highly important in developing an accurate and dynamic calibration model.

Dr. Lewis describes how Pleasantville’s network collocated the nodes with regulatory sensors for a month prior to their deployment and continues to have one node permanently colocated with the reference monitor to allow for long-term data QA/QC over the life of the project. Dr. Lewis notes how working with Clarity’s Remote Calibration model helps to reduce the amount of error in the data, and how recognizing these smaller data spikes lends important insight into granular air quality changes.

While [spikes] may not lead to going over the limit for 24 hour standards, we do see these really high spikes sometimes…[with the data] the community then has the ability to have a more accurate understanding of those spikes, and we’re able to quantify how often those 1-hour spikes happen…[and can use this data] to justify the need for a regulatory monitor in their community.”

— Dr. Lewis

Communication to & Use by the Public

There’s inherent uncertainty in the data produced by both low-cost sensors and even reference instruments. How are you managing and communicating those uncertainties in the data to the public especially if the audience is not technical?

Low-cost air quality monitoring networks can provide invaluable data findings to community members who are concerned with their local air quality; however, it is vital that the data and its associated uncertainty are communicated appropriately. Our panelists discussed their own experiences with this process. While the level of residents’ involvement differed network by network, all our speakers agreed that the most important part of this relationship is to communicate the general pollution trends in a way that recognizes the inherent uncertainty in the data. That is, communicating relative changes over absolute ones can be much more useful for the public, especially one that is less technical.

Dr. Fuller describes how drastically the degree of uncertainty in a measurement can affect how both officials and the public interpret data findings. Measurements that differ by only a few µ/m3 may mean the difference between perceived “poor” or “acceptable” air quality when compared against a standard. Because of this, Dr. Fuller advocates using low-cost sensors in a way that plays to their strength, such as measuring pollution peaks compared to ambient data.

I think a better way to frame this is in terms of talking to communities about what questions they can answer with [low-cost sensors], rather than focusing too much on the uses that we shouldn’t put them to...getting people to think about relative changes and relative differences rather than absolute ones. I think that’s a far more appropriate and informative use of these types of technologies.”

— Dr. Gary Fuller

Dr. Lewis seconds the importance of communicating relative pollution changes to the community, as well as the patterns that arise from this data. She emphasizes that the community knowing when and where air pollution is higher encourages behavior changes to avoid pollution exposure.

Dr. Lewis also notes the importance of data visualization to present the network’s findings.

Visualization of data is extremely critical for residents...being able to link the measurements to the air quality index, for instance, as a communication tool is fundamental to understanding [air quality changes].”

— Dr. Lewis

Ogletree discusses how directly measuring pollution spikes leads to positive action being taken in the community. For example, deploying low-cost sensors at a construction site allows him to bring out inspectors any time there is a significant spike in the data. Leveraging the relative changes that can be measured with low-cost sensors helps to support pollution-reduction behavior within the community while reducing inaccurate perceptions of data uncertainty.

Community Engagement and Empowerment

What are these sensor networks enabling in the communities they are used in? How does the availability of local air quality data help to educate citizens and frame the conversation around air quality? Can you provide some examples of positive benefits and changes resulting from data from these networks?

Low-cost sensor networks allow community members concerned about their local pollution levels to have access to real-time data with which they can frame their understanding of air quality. This data may also be leveraged to support local policy and behavioral change within their community.

Dr. Lewis explains the close connection that community members have with their sensors in Pleasantville, Houston, Texas. Through a participatory action project, local residents get a vote on where these sensors are placed throughout the community. The project has continued to see the benefits of close community engagement.

The community has seen the power of this participatory interest and action by its community leaders...Any time there is a fire or some sort of industrial event, they look to these networks to try and understand how it’s impacting their health…[this is] a positive impact of increasing education and awareness.”

— Dr. Lewis

In turn, low-cost air sensor data gave residents the evidence they needed to advocate for the placement of a federal monitor in the community as part of the 2021 air quality monitoring plan under the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ).

A substantial benefit of close community engagement with a low-cost sensor network is the education and awareness that this local data availability generates.

Education is, to me, the greatest initial benefit in raising awareness [using low-cost sensor networks]...and then how they’re using this [data] to advocate for asthma programs, education in their schools and with their residents…[this is] the initial first greatest benefit.”

— Dr. Lewis

Dr. Fuller also sees the strengths of low-cost sensors in providing additional data to frame residents’ concerns about local air quality issues, especially when residents suspect high air pollution in a certain area but can support it using data. He shared the example of a small village south of London that was concerned about NO2 pollution coming from the main road in their town, and how residents were able to conduct their own community NO2 measurement project to prove to regulatory authorities that these levels exceeded the standards.

Hybrid Networks

How do you see low-cost sensors being used in the air quality monitoring networks of the future? Can you provide examples of how data from such networks can be effectively integrated with larger monitoring plans?

Our panelists all agreed that they see a future of low-cost air sensors being used within hybrid network designs. Hybrid networks allow for the strengths of low-cost air quality sensors to complement reference-grade monitors and fill in the gaps that exist with traditional, more costly infrastructure. Within these networks, low-cost sensors can indicate general pollution trends that may be corroborated with reference-grade monitors, and they provide a way to directly engage community members in their local air quality.

Ogletree shared the value that low-cost sensors bring to provide ground-level, granular air quality measurements.

[A]s time goes on we’ll see more [hybrid] networks and more collaboration putting networks [of low-cost sensors and reference-grade monitors] together...so that we can very systematically increase the amount of data that is available for use by regulators to inform how they see air quality across a larger region.”

— Michael Ogletree

Dr. Fuller agreed that low-cost sensors play an important role within the larger air quality monitoring space in bringing data access and awareness to individuals. He explained that having a local air quality monitoring network can make air quality monitoring more of a bottom-up, rather than top-down, approach which empowers residents through their involvement. In turn, residents become more encouraged to enact behavioral change as well as advocate for policy change, in some cases.

I’m really excited to see what difference it will make in a community by people having their own local results. We often say air pollution is an invisible killer...just for a community to be able to say...this is when air pollution is worse, what difference will that information make.”

— Dr. Fuller

The future of air quality monitoring in urban environments

Low-cost air quality sensors are an increasingly useful tool for the air quality monitoring industry, especially when implemented in conjunction with reference-grade monitoring equipment to form a hybrid network. While some challenges do exist with the use of low-cost sensors, we can look to the experience of those who have already successfully implemented low-cost monitoring networks to best leverage the strengths of low-cost sensor technology.